Measuring the Cosmos: The Legacy of Ancient Indian Astronomical Instruments

- gauri gupta

- Nov 15, 2024

- 3 min read

In the ancient world, when the night sky was a canvas of endless wonder, humanity looked up to the stars with both curiosity and awe. The stars, for our ancestors, were not just distant lights; they were messengers, harbingers, guides. And to read these celestial messages, our forebears crafted instruments of extraordinary precision. In India, this art of measuring the heavens was a sacred endeavor, blending science with spirituality.

One such marvel was the Ghaṭī-Yantra – the water clock. A simple yet sophisticated device, the Ghaṭī-Yantra consisted of a hemispherical copper bowl with a tiny hole at the bottom. When placed on the surface of a water-filled basin, it would gradually fill and sink, precisely timing the cycle of a day and night. This was not just a tool; it was a symbol of the rhythm of existence, echoing the heartbeat of the universe. For centuries, the ghaṭī punctuated life in India, from royal courts to bustling town squares, marking the passage of time with its gentle submergence.

A Birth, A Water Clock, and of Knowledge

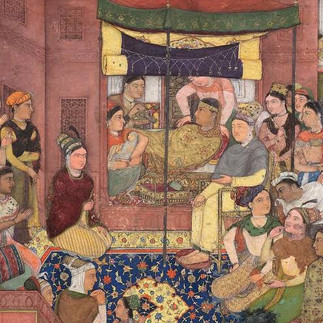

The Ghaṭī-Yantra’s importance can be seen in the art of the time, most notably in the miniature paintings that adorned the royal Mughal courts. One remarkable painting, now housed at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, captures the birth of Salim, the future Emperor Jahangir. In this painting, we witness an intimate scene outside the harem, where astrologers gather around the newborn, carefully noting his horoscope under the glow of flickering lamps. The water clock, beautifully ornate, stands prominently on the carpet in front of the astrologers – a silent observer, marking time with its steady rhythm.

Here, the ghaṭī-yantra is not merely a scientific tool; it becomes part of a larger narrative of cosmic timing and divine alignment. The placement of this water clock in the scene is symbolic, emphasizing the belief that the stars and time itself bear witness to the birth of emperors. The astrologers rely on this ancient device, not just for its practical utility, but as a symbol of cosmic order – an affirmation that this child’s destiny is woven into the fabric of the universe, measured by both the celestial bodies and the earthly rhythm of water filling a bowl.

This miniature, with its vivid depiction of the ghaṭī, provides a rare glimpse into the intersection of art, science, and spirituality in the Mughal court. It suggests that scientific instruments were not isolated from the cultural and religious lives of the people but were seamlessly woven into the symbolic fabric of royal ceremonies and rituals.

The Role of Manuscripts: Preserving Scientific Knowledge

But how did our ancestors know the precise timings, the angles, the distances? This is where the role of ancient manuscripts becomes central. Unlike today, where knowledge is accessible at the swipe of a finger, wisdom in ancient India was locked within the leaves of palm manuscripts. In the sixth century, astronomers like Āryabhaṭa documented their observations and insights in texts such as the Āryabhaṭasiddhānta, which laid the foundations for many instruments.

These manuscripts, like the Yantraprakāśa by Rāmacandra Vājapeyi, acted as both instruction manuals and theoretical treatises. They not only described how to build instruments like the ghaṭī, śaṅku (gnomon), and cakra (disc), but also explained the mathematical and philosophical reasoning behind them. Through these texts, Indian astronomers emphasized that astronomical learning was incomplete without the tangible, tactile experience of instruments. Just as the ghaṭī’s sinking marked the march of time, these manuscripts recorded the progression of knowledge across generations.

The Crossroads of Cultures: Islamic and Indian Astronomy

By the 14th century, Indian astronomers began interacting with Islamic scholars, who brought their own legacy of celestial study. The two traditions merged, influencing one another profoundly. The Yantrarāja, penned by the Jain monk Mahendra Sūri at the court of Fīrūz Shāh Tuḡlaq, is a testament to this cross-cultural exchange. It showcased Indian instruments alongside Islamic observational techniques, enriching both traditions.

The Ghaṭī’s Silent Journey Through the Ages

This ancient clock remained relevant for centuries, even finding use in temples and dargahs across India and beyond. It was present in Buddhist monasteries, royal courts, and later, Sufi shrines – a silent companion to rituals, a marker of devotion. Today, some remnants can still be found in museum collections, though most have vanished, victims of time and repurposing of metal. The manuscripts, however, endure. They remain silent witnesses to an age when the act of measuring the cosmos was akin to measuring the self, as each observation brought the observer closer to the rhythm of existence.

So next time you see the night sky, remember the ghaṭī-yantra, the silent sinking bowl that once marked time in a timeless world, and the manuscripts that preserved its legacy. In their silence, they remind us of an ancient truth: the universe is a grand clock, ticking with each star’s light, waiting to be read, understood, and cherished.

Comments